|

|

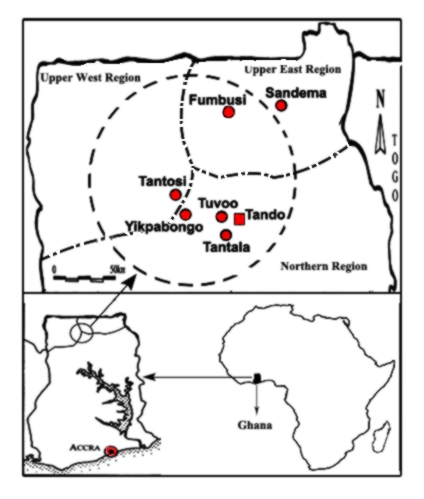

Fig. 1. Tando and Koma Land archaeological region |

Jobila M. Zakari (2011)

Excavations at Tando: A Contribution to the Archaeology of Koma Land of Northern Ghana

Abstract

This research was conducted as part of the requirement for the Master of Philosophy at the University of Ghana. The study sought to investigate aspects of the material culture of Tando and its relationship with material culture from other sites within the Koma Land archaeological region. The study revealed archaeological relics, mainly potsherds, terracotta art objects, stone tools, smoking pipes whose significance shed light on trade network, ancestral worship and settlement history of both the present-day and ancient people of Koma Land.

Introduction

Northern Ghana is characterized by soil preservation of sculptural and lithic objects and patchy iron ores which have been a focus of archaeological and anthropological research since the second half of the twentieth century AD. On the plains, and in particular, within the basins of the Kulpawn and Sisili rivers, archaeologists have labeled an area called the Koma Land Archaeological Region consisting of stone circles and settlement mound/sites and covering a boundary of 100 x 100km (Kankpeyeng and Nkumbaan 2009: 195). These mound/sites are closely distributed amongst both living and abandoned settlements. While the former includes Yikpabongo, Tando, Gwosi, Kundugu, Tantala, Yiziesi, Daboziesi, Tovoo, Tantuosi, Wiesi, Fumbisi, Zugkpeni and Nangruma, the latter are Zoboku, Kpikpirigu, Baranya and Fagusa. These settlements occupy parts of the three Northern Regions of Ghana, namely Upper East, Upper West and Northern.

|

|

Fig. 1. Tando and Koma Land archaeological region |

The Koma Land Region (Fig. 1)

The Komaland archaeological region is characterized by four main ethno-linguistic groups, namely ‘Konni’ (Kankpeyeng et al 2013: 478; Kröger and Saibu 2010: 1), ‘Mampruli’ (Rattray 1932; Zakari 2010: 2), ‘Sisali’ (Swanepoel 2004, 2008: 12) and ‘Buli’ (Kröger 1982). The people of Tando speak Mampruli, a language of the Mamprusi ethno-linguistic group. Mampruli is one of the Mole-Dagbani languages spoken in parts of Ghana, Burkina Faso and Togo (Naden 1985). The ‘Mampru Sabli’ (Black Mampruli), spoken by the people of Tando, varies slightly semantically, but genetically it is similar to the Mampruli spoken in other places of ‘Mamprugu’ such as Walewale, Gambaga, Nalerigu, Lengbinsi.

The ‘Mampruli’ and that of their close neighbors, namely, Koma, Bulsa and Sisala peoples belong to the same sub-group of the Gur language. Studies have revealed that the Kingdom of Mamprugu developed as early as 1475 AD (David 1987). The Koma Land archaeological region is drained by the Sisili and Kulpawn rivers, with several streams that run dry in the dry season (November to June). The area has been given the derogatory name ‘overseas’ due to its poor road networks (Anquandah 1998:7) and intense floods from the Sisili and Kulpawn rivers, tributaries of the White Volta River. These environmental complications make it impossible to cross the rivers without a boat, and strictly limit the inhabitants’ movement during the rainy season (June-August).

Over the years, the Koma Land archaeological research has unraveled divergent material culture with varied interpretations. Among these archaeological finds are terracotta figurines, ceramic discs, potsherds, stones, daub, flora and fauna remain and tobacco/smoking pipes (Anquandah 1998, 1987; Anquandah and Van Ham 1985; Kankpeyeng and Nkumbaan 2008, 2009; Zakari 2010: 30). From the 6th to the 12th century AD the ancient Koma culture flourished in this region (Insoll et al 2012: 26), with their cultural adaptation sheathed in settlement mounds and stone circle mounds (Anquandah 1998, 1987: 173-174; Anquandah and Van Ham 1985; Kankpeyeng and Nkumbaan 2008, 2009; Zakari 2010: 30). The distinctive feature of the stone circle mounds is that their makers are still unknown.

Archaeological Survey

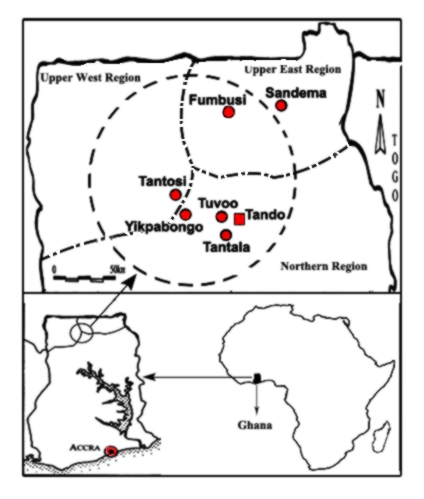

The approach to this archaeological study at Tando was eclectic; it involved archaeology, oral tradition, ethno-history, geography and ethnography. Prior to the excavations, there was a surface survey in the entire village of Tando. This employed a method known as spoked wheel reconnaissance survey. Using this technique, a datum point was located and sampling units were identified. These units were evenly arranged along eight (8) radiating transect lines positioned at angles of 45 degrees. Four (4) workmen from the research team lined up at arm’s length and walked from the datum point to the extreme fringes of Tando. The team did indeed collect artifacts (terracotta figurines, tobacco pipes, stone implements and potsherds) and recorded features (mounds) with a GPS unit. Previous archaeological studies in the village of Yikpabongo, 9 km north-west of Tando, have brought to light two forms of mounds, namely stone circle mounds (Anquandah 1998; Kankpeyeng and Nkumbaan 2008) and settlement mounds (Kankpeyeng and Nkumbaan 2008). Like in Yikpabongo, the mounds in Tando were also comprised of stone circle mounds and settlement mounds. Whereas the stone circle mounds (whose makers are still unknown in the archaeological region) reveal evidence of terracotta figurines, potsherds and stones or impressions of stones on their surface, the settlement mounds have manifested pieces of local ceramics and daub on their surface and are believed to be associated with the present-day peoples. Excavations were conducted on one of the settlement mounds (N10̊ 11' 13.6" W001̊ 30' 46.4") at Tando. On the mound, two pits were dug measuring 2m x 2m and 3m x 1m (Fig. 2).

|

|

Fig. 2. Soil profile of the west wall of trench 1 |

Overall, the excavations and surface collections of the reconnaissance survey uncovered 3702 potsherds, 38 terracotta figurines, 4 tobacco pipes and 15 stone implements representing 98.5%, 1%, 1% and 4% respectively of the total artifacts. The terracotta figurines have enriched our understanding of

|

|

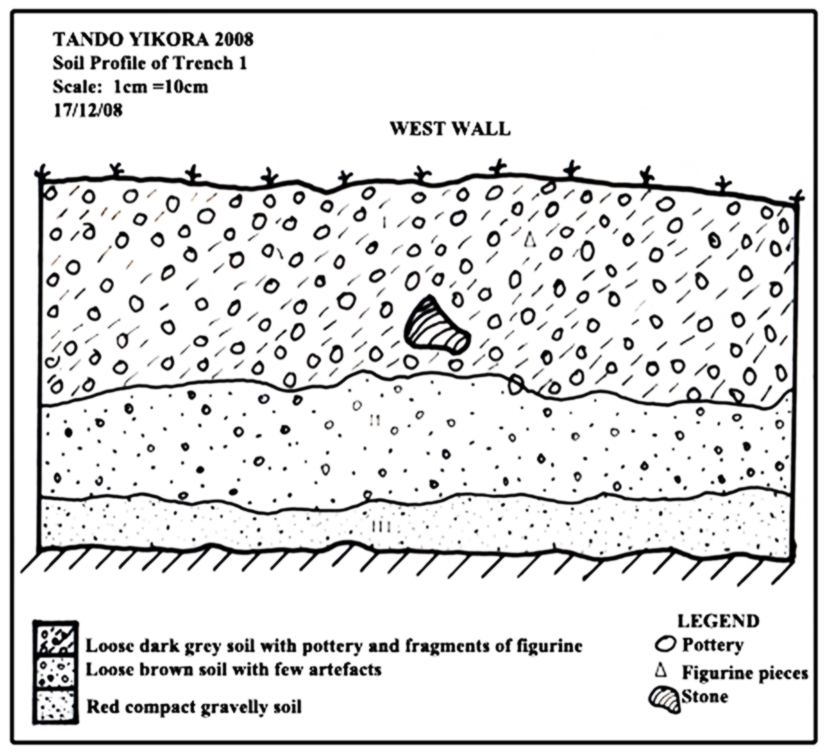

Fig. 3. Impressions of cowrie shells on a terracotta objects |

Tando and its environs as a probable branch of a regional trade route during the Trans-Saharan Trade between West Africa and North Africa. For instance, a terracotta ritual object came to light with stamps of cowrie shells (Fig. 3). The significance of these stamps has been mentioned in the historical records of Medieval Islamic Sudan as products of export from Sijilmasa to earlier states of West Africa such as Kumbi Saleh (ancient Ghana), Gao, Jenne, Kouga and others (Anquandah 1998:78).

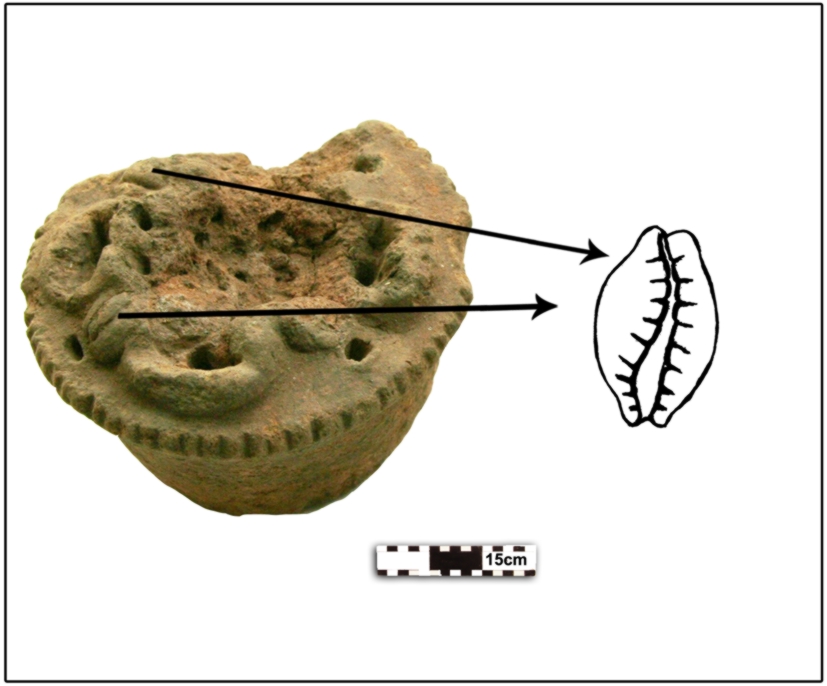

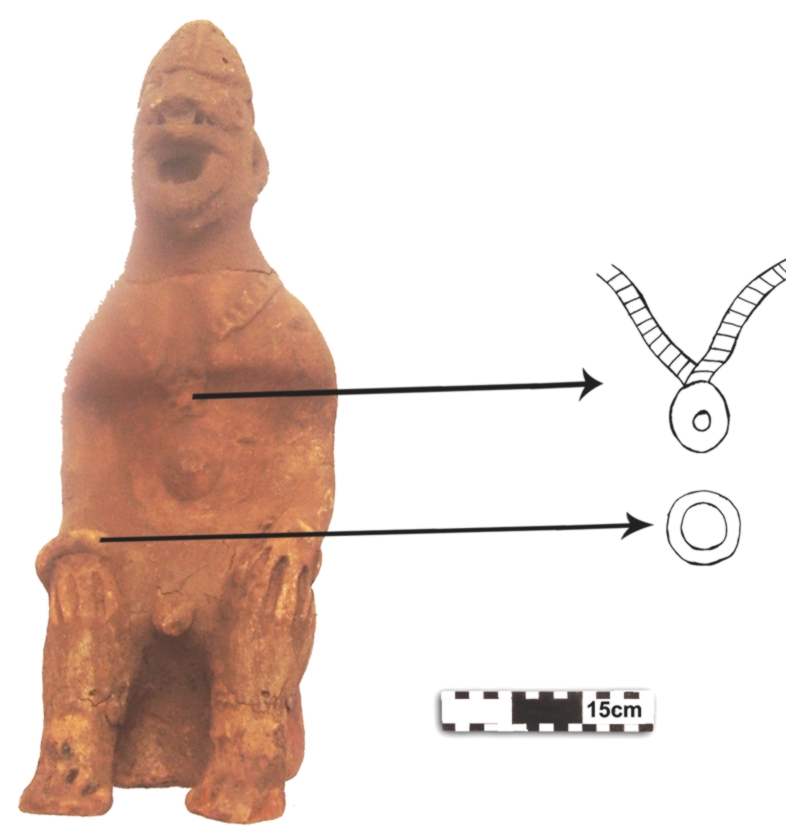

Whereas complete pieces of terracotta figurines were collected during the spoked wheel reconnaissance survey, the excavations uncovered potsherds, stone objects, tobacco pipes and other artifacts from the archaeological record. The figurines have no connection with the present-day people of Tando, thus indicating that the sites at Tando were culturally adapted to the savanna area of northern Ghana and were occupied by different groups of peoples at different times. The works of art known to the present-day people of Tando consist of wood carvings imitating shapes of the ancient terracotta figurines. Some of the carved pieces are significantly tied to the cosmologies of the Tando peoples, some of whom would periodically perform sacrifices to serve the needs of cosmic powers. Among the ancient art objects recovered from the archaeological survey at Tando were 7 complete figurines and 9 fragments. Ornaments are common on Koma Land art objects, some of them referred to as symbols of good luck and others capable of warding off evil, the former; concept of power and instrumentality that is abundant in the product of wildness (Fig 4).

|

|

Fig. 4. Terracotta art object from Tando |

The tobacco pipes recovered from Tando were made of clay. They were examined based on Ozanne’s (1962) chronological (rather than typological) classification of the tobacco pipes’ design. These pipes were established as locally manufactured products beginning in the 18th century, a time when the people of Tando probably migrated from Kpikpirigu to their present homestead (Fig.5).

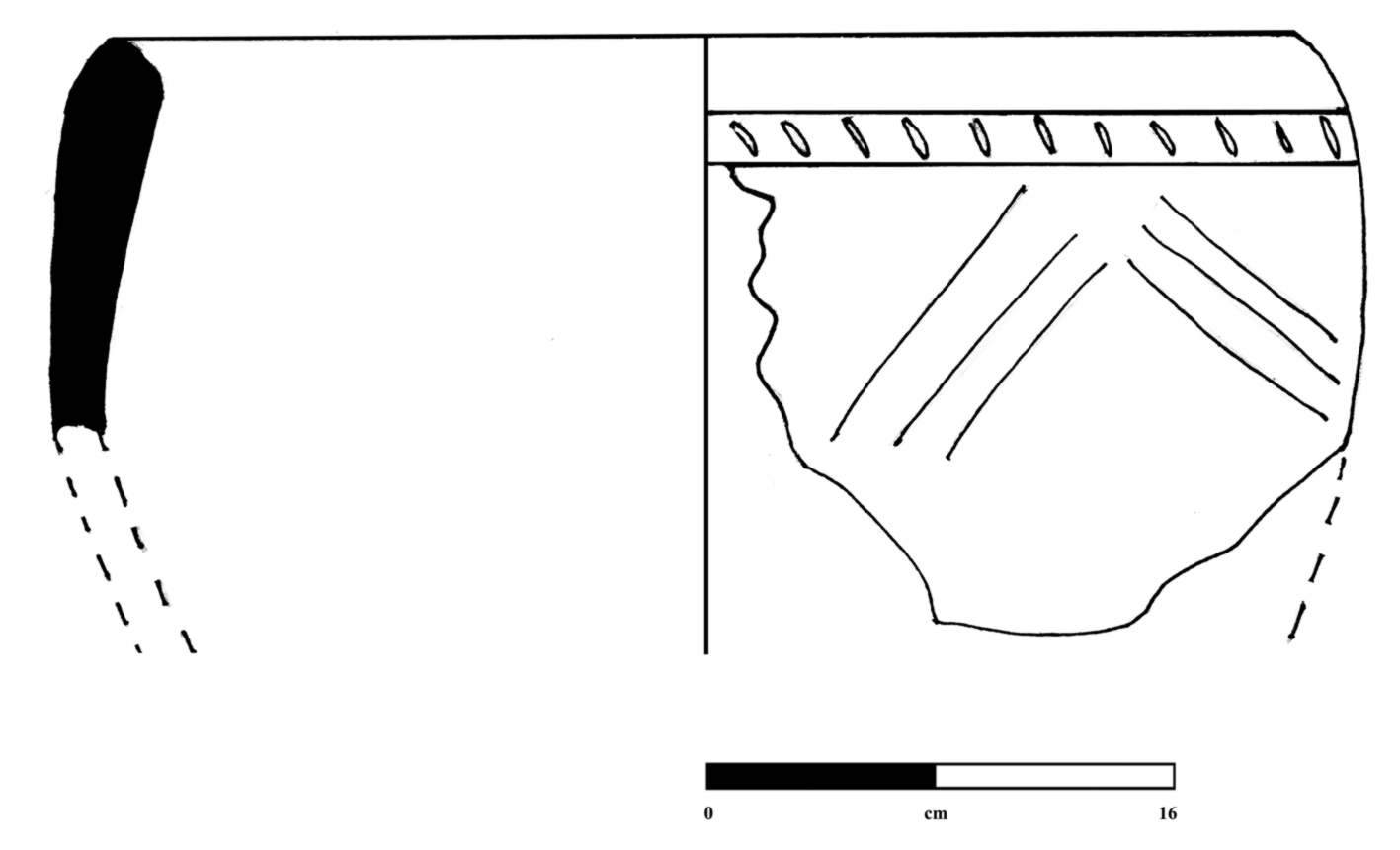

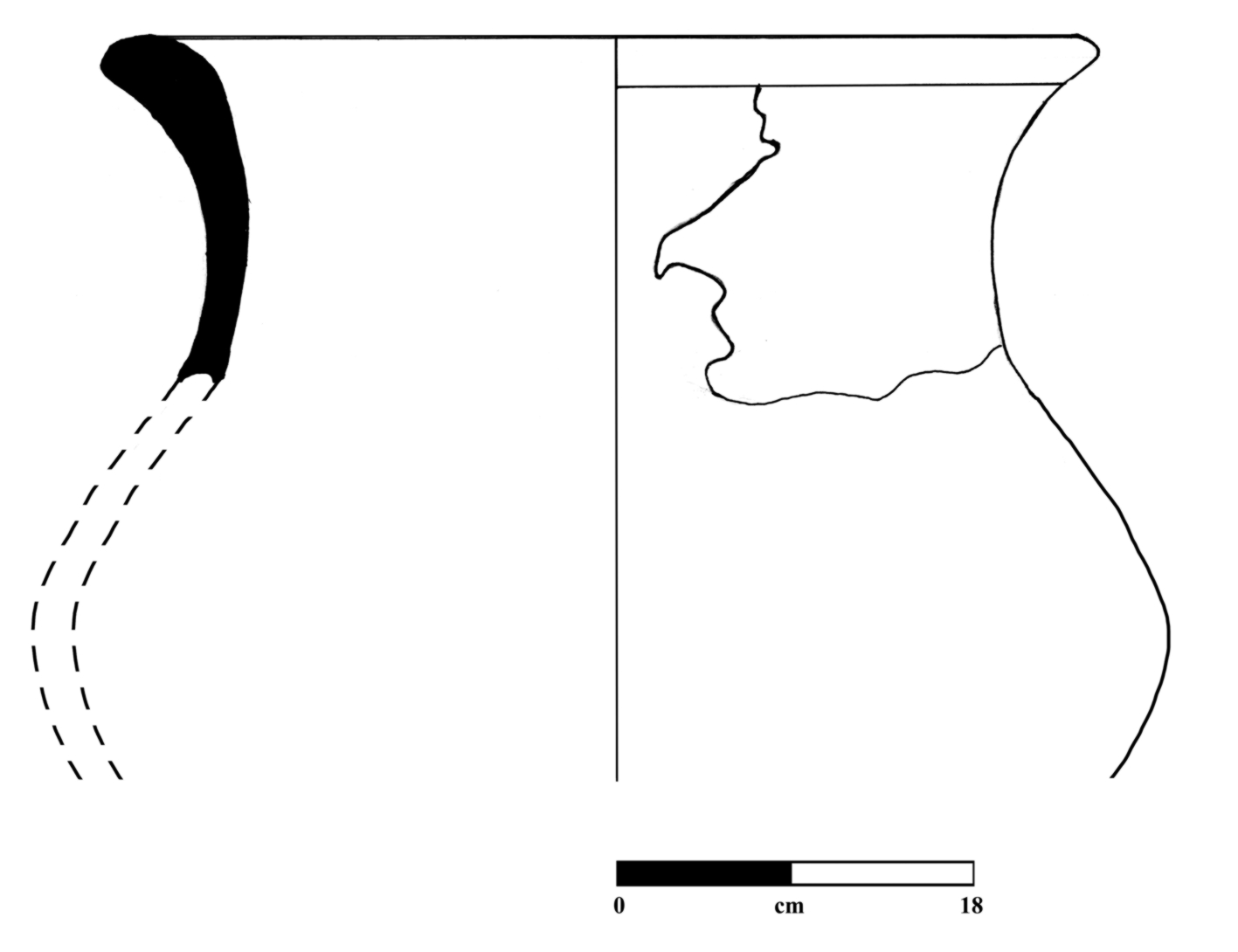

The decorations of pots recovered from Tando provided insight into trade networks and technological evolution of the people of Tando and beyond. These decorative characteristics were roulette, wavy impression, incision, perforation and punctuation. Some of these pots also showed the attributes of multiple decorations (e.g. Punctuation with wavy impression and incision with cord roulette). An observation of rim types, body types and base types of the pot sheds light on their utilitarian functions. The pots or vessels from the archaeological record complemented by ethnographic observation revealed evidence of their being used for cooking, carrying local alcoholic beverages (dazio) from one point to another, water storage, eating and for ritual practices (Fig. 6, 7, 8 and 9).

|

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 5. Smoking

pipe from Tando |

Fig. 6. Eating vessel from the ethnographic context in Tando | Fig. 7. Eating vessel from the archaeological record | Fig. 8. Local beer

serving

pot from the domestic space of Tando |

Fig. 9. Beer pot from

the archaeological record at Tando |

Conclusion

This study has provided insights into diverse cultural practices of the settlers of Tando through time and their relationship to people across the archaeological region and the broader West African Region. It has unraveled evidence attesting to how commercially-minded Mande-speaking traders travelled to the forest margins of Ghana for goods. The relevance of the functions and the decorations of the pots from Tando has broadened our understanding of contacts with other neighboring groups in northern Ghana. The establishment of contacts in northern Ghana and beyond has also enhanced our understanding of the spread of cultural tradition and identity construction within the sub-region over time.

Bibliography

Anquandah, J., 1982. Rediscovering Ghana’s Past, Longman Group Limited.

Anquandah J. 1987. The Stone Circle Sites of Komaland, Northern Ghana, The African Archaeological Review, 5: 171-180.

Anquandah, J. 1987. Investigating the stone circle mound sites and art works of Komaland, northern Ghana. Nyame Akuma 27:10-13.

Anquandah, J. 1998. Koma-Bulsa- its Art and Archaeology. ISIAO, Rome.

Anquandah, J. 2002. Koma-Bulsa Culture, Northern Ghana. Arts and Culture, 3: 113-129.

Anquandah, J. and Van Ham, L. 1985. Discovering the Forgotten 'Civilization' of Komaland, Northern Ghana, Rotterdam.

David, C. D. 1987. Then the White Man Came with His Whitish Ideas...": The British and the Evolution of Traditional Government in Mampurugu. The International Journal of African Historical Studies 20 (4): 627-646.

Insoll, T., Kankpeyeng W. B. and MacLean R., 2007. Excavations and Surveys in the Tongo Hills, Upper East Region, Ghana. July 2006. A Preliminary Fieldwork Report. Nyame Akuma 67: 44–59.

Kankpeyeng W.B. and Nkumbaan N. S.. 2008. Rethinking the Stone Circles of Komaland a Preliminary Report on 2007/2008 Fieldwork at Yipkabongo, Northern Region, Ghana. Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology, 74:99.

Kankpeyeng W. B and Nkumbaan N. S. 2009. Ancient Shrine? New Insights on the Komaland Sites of Northern Ghana: A Preliminary Report on the 2007/2009 Fieldwork at Yikpabongo, Northern Ghana,. In: Insoll. T. (ed) Current Archaeological Research in Ghana: Archaeo-Press, Oxford, Monograph Series 2, pp 95-102.

Kröger, F. 1982. Ancestor Worship among the Bulsa of Northern Ghana. Klaus Renner Verlag, Hohenschaftlarn bei München.

Kröger, F. and Saibu, B.B., 2010. First Notes on Koma Culture: Life in [a]Remote Area of Northern Ghana. Lit Verlag Berlin.

Naden, A., 1985. Language, History and Legend in Northern Ghana. Unpublished Seminar Paper, History Department, University of Ghana.

Ozanne, P.C. 1962, Notes on the Early Historic Archaeology of Accra. Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana 6: 51-70. Rattray, R. S., 1932. The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland. Oxford.

Shinnie, P.L. and Ozanne P.C. 1961. Excavations at Yendi Dabari. Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana 6: 87-118.

Swanepoel, N. J., 2004. "Too Much Power is not Good" War and Trade in Nineteenth Century Sisalaland, Northern Ghana. Unpublished PhD Dissertation, Syracuse University.

Swanepoel, N. J. 2008. View from the Village: Changing Settlement Patterns in Sisalaland, Northern Ghana. International Journal of African Historical Studies, 41 (1): 1-27.

Zakari, J. M 2010. An Archaeological Investigation of Tando; Unpublished Mphil Thesis Submitted to the Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies, University of Ghana.